(ESSAY) Where does all the colour go? by Luke Roberts

- Luke Roberts

- Feb 15, 2022

- 8 min read

Luke Roberts traverses the temporal and transitory nature of colour, revealing both the barriers of language and our creeping digital world. Through the visual works of Sager-Nelson, Balke, Sickert and Vekemans, alongside the words of Virginia Woolf, Olga Tocarczuk and glitch theorist Rosa Menkman, Roberts opens up the complexity of what colour can offer us, whilst questioning the effects of the perceived perfect clarity we experience on the screen.

There is, probably, somewhere, written a short story about a little old man, in a dusty, bare flat, who sneaks out every night with his little grey sack. He steals into the dusk, just as night rears its head, and gathers in all the world’s colours, thread by thread. Dragging them — slowly, carefully — from their comfy fixed homes, to settle side-by-side in his strained hessian bag. Before morning, he polishes and preaches — much like Krzhizhanovsky’s collector of cracks — to each and every colour, every shade, until — as light threatens to creep under the dawn — they are left to scamper back to the place of their briefly colourless dwellings.

Of course, anyone who has ever walked the world at night knows already this story. It is the noctambulist’s secret: colour has fled, and something else stands in its place. What intrusive light there is in such darkened hours twinkles and bounces from the surfaces it is not supposed to, revealing colours that are unfamiliar and lacking.

But still the memory endured that the earth we stand on is made of colour; colour can be blown out; and then we stand on a dead leaf; and we who tread the earth securely now have seen it dead. Woolf, The Sun and the Fish (1928)

The proof that such a tale matches our experience of colour is in the twilight — a time when it seems as if the worldly colours have given up trying. With a whimper they tumble into larger and larger shadows, struggling to hold their own against an emerging, universal mingling. A dinner guest of Woolf once stated: ‘for though the life of colour is a glorious life it is a short one. Soon the eye can hold no more; it shuts itself in sleep’. In fact, surely, it would seem more accurate to say that it is the colours themselves that shut their radiance away; the eye continues to search, desperate and futile.

All colours begin to slide to one totality: exhaustedly giving up their semblance of determinacy and becoming simultaneously under- and over-determined. It is a reality captured in the suggested vibrancy of Sager-Nelson’s colourless Nocturne, or the golden greys and roaring shadows of so many of Balke’s epic landscapes.

Left: Nocturne, Olof Sager-Nelson; Right: The North Cape by Moonlight, Peder Balke.

Really, it must be said that our language lacks a colour: a term for this natural universal that overcomes the world in the incomplete absence of light. What we might otherwise be tempted to divide up and demarcate under terms such as ‘dark-red’ or ‘dark-green’ must surely find a more fitting description as some differing shade of indeterminate dusk.

It’s strange how the Night erases all colours, as if it didn’t give a damn about such worldly extravagance. Tokarczuk, Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead (2018)

It’s not without precedent. The Welsh term ‘glas’ once signified a vast range of colours, from blue to green to silver to grey. Now it just means blue. Language is a barrier to our genuine understanding of what colour is — it clouds our experiences by seeking concrete constants when all that really exists is changeable, vulnerable. But language is not the only threat: the creeping digital world, that in its words and actions dictates a voracious desire to envelope the natural, poses a new threat. To better understand it, it becomes necessary to define the indefinable admixture.

This is easily done. Our experience of colour out there in the world — let us call this primary manifestation, Authentic colour — is that of something temporal and transitory: a unitary attribute. We meet Authentic colour at all times as something in the process of fleeing: both from view (at the whim of the light) and from the determinacy that our language demands of it. In fact, the flexibility of our language — the breadth of our categorisation — indicates a natural predisposition that finds us appreciative of colour’s true elusiveness.

Darkness offers one particularly temporal perspective on our experience, but there is no reason not to look to the more exotic instead. Orange, for example, is an especially transitory colour: nestled quietly between the primary reds and yellows into which it is permanently at risk of quickly fading.

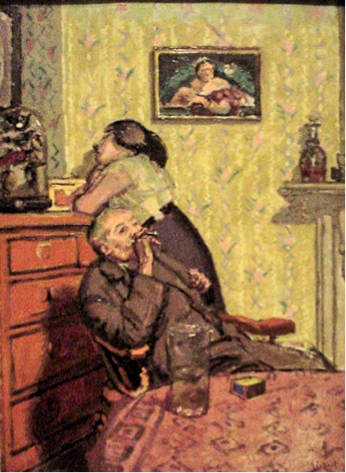

Top left: Minnie Cunningham at the Old Bedford, Walter Sickert; Top Right: Le Buevar, Bruno Vekemans; Bottom Left: En Pensée, Bruno Vekemans; Bottom Right: Ennui, Walter Sickert.

When looking to understand the nature of Authentic colour, it would be meaningless to talk of categorisation and transience in the case of works in monochrome, for there it is clear that our language lacks nuance: in these cases, simple terms of relation seem up to the task. However, in those works that merely have a sense of being monochromatic — despite really in reality being constituted of a true spectrum of colour — it becomes possible to truly come to understand Authentic colour’s nature.

Much of the work of Bruno Vekemans can serve such a purpose. Le Buevar and En Pensée are evidently works of orange (or yellow?), and yet just a rough inspection reveals a great deal more: even the bottle’s blue eventually becomes lost in the shadowy oranges and the emptiness of the individual’s clothing.

Looking for other examples, Sickert goes further. In discussing a then recent exhibition of his works, a dinner guest of Victoria Woolf claimed:

We shall very soon lose our sense of colour… Colours are used so much as signals now that they will very soon suggest action merely — that is the worst of living in a highly organised community. Woolf, Walter Sickert: A Conversation (1934)

Woolf dismisses it as exaggeration, and yet it is difficult not to find this loss in Sickert’s Ennui. Identification of any particular colour in this extreme case would be meaningless, with the mood sitting over and above the scene like that of some waking dusk: the colours roll over one another, at once different, at once the same. Alternatively, in the instance of Minnie Cunningham at The Old Bedford, the range of colours is subsumed by the all-consuming punch of Red. The background is tinged with a tone that, on any scientific spectrum, could never be adjacent. There is a sense of drift, with all colour slowly falling upon the unbounded central tone.

It doesn’t need saying that, if you were to see any one of these images in their actual, four-walled environments, they would look different. A quick search for Sickert’s Minnie Cunningham, is some proof of this, with her appearance cast vastly different in each and every occurrence. To say that a digital image and that ‘Authentic’ colour which we experience in the ‘real’ world are different is to say nothing much at all, but it is important to acknowledge the foundational processes — beyond their respective immanent appearances — that make them different in the way that they are.

The contrast is between something lacking and something lacking-a-lack: between something that is characterised by its temporality — by the blurriness of what it is and what it is not — and something fixed, complete and permanent. That these latter characteristics describing digital colour are a façade is irrelevant; that its being fixed and whole is a momentary illusion, at risk of crashing down at any moment, does not provide an escape from its being fundamentally intransitory. Digital colour lacks temporality, indeed, that is the only thing it can be said to lack.

In the process of its digital rendering, colour — if it can meaningfully be said to be capable of undergoing such a transition at all — necessarily is stripped of its original nature. It becomes something determinate; something fixed and carefully categorised by its sequence of numbers and letters; something complete. Something subject to the whims and wishes of those that view it and stripped of the ability to disappear of its own accord. It becomes a-click-away: atemporal and in an entirely singular form. If we were to give a name to such a state, we might give it that of Available.

And the snow-white sheet of paper did remain pure and chaste for ever — pure and chaste — and empty. Gibran, ‘Said a sheet of snow white paper…’ (1920)

The contrast with Authentic colour could not be starker. Elsewhere, unrelated, Kierkegaard describes ‘the kind of familiar, intimate impression which a lake surrounded by forest’ produces as something ‘large enough to separate and unite at the same time’. Something ‘the sea cannot’. Like the open sea, inherent in the structure of the Available is the lack-of-a-lack: the not-itself that is a fundamental aspect of Authentic colour, that defines itself by its shifting and eluding. In being so constituted, the Available closes itself off.

Of course, a ‘colourful’ screen can turn ‘dark’, an image can be closed. But this ‘darkness’ is mimicry — a dark screen or an absent image does not have the fleeting absence that defines Authentic darkness: it is a tempered void rather than something in open flux.

The work of Rosa Menkman brings this state of affairs into sharp focus. Her Glitch Studies Manifesto highlights the vulnerability of the digital medium — the fact that ‘the static, linear notion of information-transmission can be interrupted’. She reveals that Available colour is in fact Vulnerable-Available: it is constantly at risk of being exposed as a thin actor and as something that in some significant way cannot truly be said to be there.

Here, though, it is important to note that the terms Authentic and Available — with the latter settling under the wider umbrella of the Inauthentic — are wholly value neutral. They are descriptions of exclusive spheres rather than castings of judgements. However, if we admit (with no need for justification) that both are important, we must acknowledge the threat that one poses to the other.

Yet the timeless in you is aware of life’s timelessness. Gibran, The Prophet (1923)

Our experience of digital, Available colour is a modern experience and one that, for the reasons described above, is radically different to its primordial, Authentic forerunner. But, beyond this, it alters our experience of colour in its most general sense: leading us to become accustomed to, and expectant of, a strict categorisation, perfect clarity, and total experiential subjugation. As we are further exposed to the Available (even before we make consideration of the apparently incoming metaverse (something I will not be doing)), we move closer to a world of clearly determined colour and category, and further from the under- and over-determined realities of colour’s shifting nature.

Everything in its right place; everything left to be as it is. If we lose sight of Authentic colour’s nature — a fundamental aspect of our current visual experience — we lose sight of the transitory and indeterminate and temporal aspects of our own human experience: that is, what it is to be who we are; in reflections we always find ourselves.

After all, it is no coincidence that colour, as a property, falls under the category of an accident.

Haven’t you seen how a bubble comes up on the water? As long as it lasts and is whole, what colours play upon it! Red, and blue, and yellow — a perfect rainbow or diamond you’d say it was! Only it soon bursts, and there’s no trace left. And so it was with those folks. Turgenev, Old Portraits (1881)

~

Text: Luke Roberts

Images: Cover Image: glitched version of Nocturne (Olof Sager-Nelson), by Luke Roberts, Following Images: Olof Sager-Nelson, Peder Balke, Walter Sickert, Bruno Vekemans

Published: 15/02/22

Comments