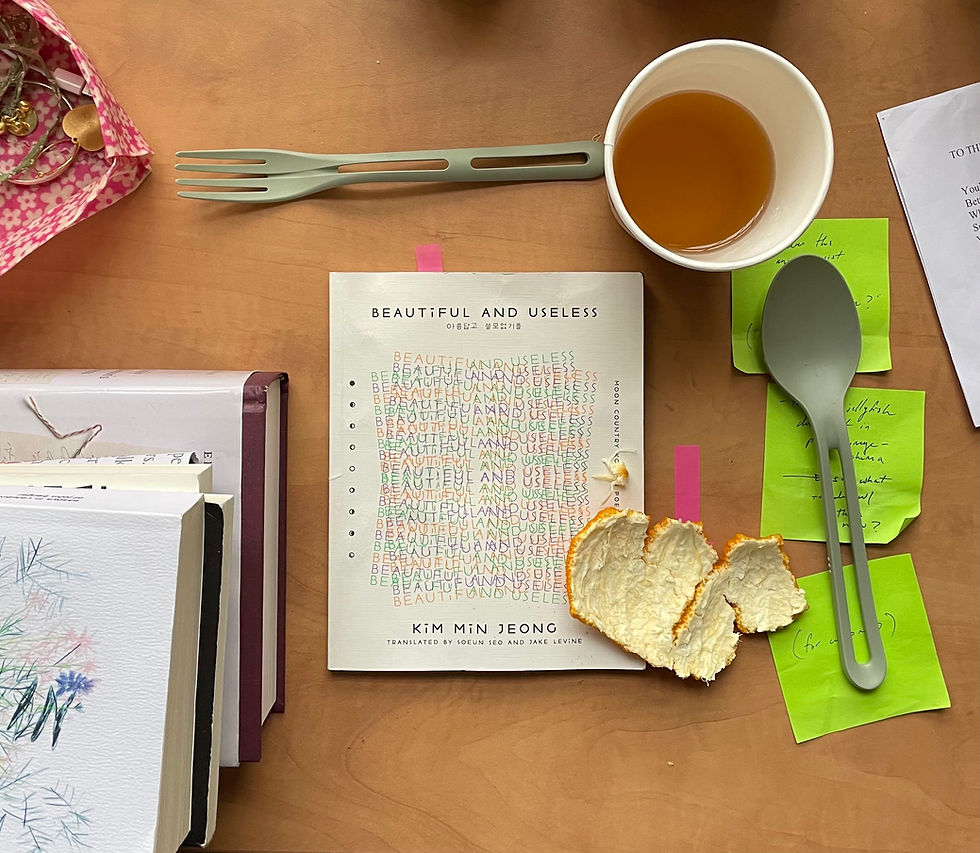

(REVIEW) Beautiful and Useless by Kim Min Jeong (trans. by Soeun Seo and Jake Levine)

- Katherine Franco

- Apr 13, 2021

- 7 min read

Katherine Franco delves into the provocations of Kim Min Jeong’s stunning new collection, Beautiful and Useless (2020), published by Black Ocean and translated by Soeun Seo and Jake Levine. A book which questions what poetry does, poetry’s value, its use, its beauty and yes, uselessness. By exploring the sharp wit, ‘kingly kidness’ and ‘bastardised girlishness’ in Min Jeong’s lines, Franco considers the valences of repetition, tautology and play for an anti-capitalist poetics.

What you doing? Sharpening a knife. Is something up? I said I’m sharpening a knife. Did I do something? No. I’m just sharpening a knife. Exactly, you’re sharpening a knife.

‘Did I do something?’ Kim Min Jeong’s speaker asks midway through ‘Serenade of Excellence’, to which the other speaker replies, ‘No. I’m just sharpening a knife’. The assumption of agency –– the need to implicate oneself through asking the ‘I’-centred, ‘Did I do something?’ –– is self-interested or, at the very least, foolish. When Min Jeong’s speaker responds in the negative, she instead affirms a ‘doing’ per se.

Yet Min Jeong’s poem would not exist without the first interrogative line: ‘What you doing?’ The more Min Jeong’s speaker attempts to advocate for the ‘doing’ness of her gesture, the more she confirms its status as metaphor or rhetorical strategy via repetition. This, we recognise by the poem’s culmination, is the knife’s primary use: poetry.

To talk about ‘doing’ is one of the challenges and thrills that runs through Min Jeong’s Beautiful and Useless (Black Ocean, 2020), translated by Soeun Seo and Jake Levine. A title almost perfect for her speaker’s dismissive ‘No. I’m just sharpening a knife’: a gesture beautiful and useless through its ‘just’ness. James Joyce told us to unsheathe our dagger definitions; Min Jeong says to unsheathe our daggers.

Why do we declare daggers? Why define –– confine –– them? For whom? And at what cost? (Cost is, after all, always the question in Min Jeong’s work.) What does it mean for a poetics to be useless and beautiful? Beautiful, in its uselessness? Is such a thing possible? Or is beauty use? What is a per se poetics? These questions lie at the centre of Beautiful and Useless.

Everything has, or exists in the context of, use-value in Min Jeong’s poetics. The ajumma in ‘Smells Can’t Keep Up with Trends’, for instance, ‘picks her teeth with an empty vitamin C packet’. The suggestion: there’s no such thing as a throw-away, not just in Min Jeong’s poetics but in poetics more broadly. Like Joyce –– not an inappropriate reference point, given Min Jeong references his Chamber Music in the collection’s final poem –– Min Jeong understands the book as material object. To put a jellyfish on the page is to now sell a jellyfish, albeit two-dimensional after its translation into the written sign, or an empty second-hand vitamin C packet. Poetry is thrifty.

A first-generation poet of the Miraepa (future movement) school, Korean literature’s New Wave movement of the 2000s, Min Jeong is poetry editor of Korea’s largest publishing house, Munhakdongne. Min Jeong is (in)famous for her tendency, in the words of Seo, to ‘do all the poetry no-nos’. ‘It was sooo hard’, Seo responds to Min Jeong, in describing the process of translating her distinctive puns and word play at the Asian American Writers’ Workshop. ‘I mean, you guys did it’, Min Jeong replies in her usual matter-of-fact tone. Min Jeong is not interested in a respectable poetics, particularly the one evinced in the Korean poetic tradition, but instead ‘cramming in all kinds of words like cockroach, eyeballs, periods, clit, camel toe. I mean… my poetry, it’s not beautiful’.

Min Jeong’s most concentrated object of uselessness and beauty comes in the form of a ‘small and simple unglazed bowl’ in ‘The Trinity (Kimchi, Steamed Pork, Fermented Skate)’. ‘I can’t explain it’, Min Jeong writes of the bowl before attempting to explain it. ‘There’s no rubric / but they say / you feel it in your gut’. Beauty is useless and embodied; beauty is, more simply, uselessness. Min Jeong more explicitly refers to commodity culture in poems like ‘Mass Shipment of Spring Greens (First Day of Summer on the Lunar Calendar)’ when she writes of the Shepherd’s Purse plant, ‘Are they cheap or expensive? / Would I know if I picked them in the mountains? / Would I know if I sold them at the market?’

In ‘Women Rise at Night’, a four-part long poem in the collection, Min Jeong begins with jellyfish. ‘Snow fell / but the milky jellyfish / that were like white button-up shirts that jumped into the sea / were a bit too big / to be snowflakes’. The milky jellyfish literally won’t fit into the poem-image-schema — so what is the speaker to do with them now? The opening of ‘Women Rise at Night’ gestures toward the question inevitably asked by every poet in the face of the world: how does this animal assist me in my artistic practice? The poem’s redundancy, however, mocks this poetic tendency. Within the first ten lines, Min Jeong tires this milky jellyfish-snowflake by exact repetition. She does something of the same in the third section, describing melon as ‘the trashy melon-melon like thing’. A jellyfish is not a jellyfish but a product, for the eye’s consumption on the page. Can anything ever just be a thing? As the speaker’s mom in ‘12 Hour Marinated Poem’ says in its ultimate line, ‘Poetry, schometry. Come and peel the onions!’ Language renders itself.

Min Jeong, too, interrogates the relationship between originality and capital. Min Jeong renders her work useless, in speaking of literary history and her likely inability to say it anew. ‘But why can’t I say how it feels?’, she asks in ‘Like the Second Child of a Family with One Son, Two Daughters’. ‘Because Poet Lee Sung Bok said it already’, she curtly replies. ‘He wrote all there is to say / about the feelings that come and go. / I’m beating a drum solo on this dead horse’. Yet Min Jeong nevertheless –– evidently –– attempts to say more about the feelings that come and go. That very thing, we realise, might be beauty itself: the need to beat a drum solo even after it's been done before.

Sharpening knives allows –– or permits –– Min Jeong’s speaker to ‘bec[o]me a bitch’ by the end of 'Serenade of Excellence'. Min Jeong often traces these arcs: girls becoming bitches, skipping over womanhood along the way. Min Jeong writes of girlhood –– ‘I was a kid but not that kid. / I was a beast who wouldn’t sit on an ajeossi’s lap. / A small but powerful girl, a kingly / virgin’ –– with echoes of Diane di Prima’s ‘old longing to be a pirate, tall and slim and hard, and not a girl at all’. Min Jeong writes of a kingly kidness, a bastardised girlishness. It’s this former kingly virgin who now wields tits and dicks.

Everyone is a slut in Min Jeong’s poetry: the institution of family; politicians; literary critics; the common reader, too. Sluttiness is essential to Min Jeong’s poetic project, as well as cognition more broadly –– ‘Understanding can’t be born / without someone acting like a slut’ (Section 3, ‘Women Rise at Night’). Min Jeong exercises language –– of tits, dicks, bitches, sluts –– with the joy of a child discovering the terms for the first time. A language Min Jeong calls ‘non-poetic language’. This childishness runs through her collection, often on the subject of politics. ‘Political wrongs are so childish’, Min Jeong told Seo and Levine. ‘And the only way to call out a childish thing is to say it like a child’. Min Jeong’s politics is grounded in the strength of that kingly virgin — that beast who refuses the status quo.

In writing of use and poetry, we can consider a passage from Capital’s Chapter 14 wherein Marx examines the Division of Labour and Manufacture. Describing specialised labour, Marx writes, ‘The worker’s continued repetition of the same narrowly defined act and the concentration of his attention on it teach him by experience how to attain the desired effect with the minimum of exertion’ (Capital). Repetition. Narrowly defined. Concentration of his attention. Marx’s taxonomy is useful in considering the goal of Min Jeong’s poetry, if not poetry more broadly. Is poetry economical in its minimum exertion, its taut form, its linguistic economy, compared to something like a sprawling novel? Min Jeong’s hyper-tautological practice throughout the collection (‘…it’s nice / to be nice’ in ‘Women Rise at Night’) would suggest so. Invoking awkward tautologies is resistive to the economy of poetry. Min Jeong’s repetition of the ‘milky jellyfish… like button-up shirts that jumped into the sea’, for instance, over the course of ten lines asserts linguistic ‘exertion’. We imagine Min Jeong typing the phrase once more, even after the first use sufficiently renders the image. Or perhaps we instead imagine copy-and-pasting, if we do want to consider the possibility of ‘minimum of exertion’.

Repetition of this sort becomes anti-useful, a means of occupying more of the page without generating new linguistic values. A cyclical poetics then becomes anti-capitalist, anti-productive, in its refusal toward productive outcome. A poetics, in its commitment to say even after ‘Poet Lee Sung Bok said it already’, becomes counter-productive. Counter-product. Min Jeong’s product, all the same.

Beautiful and Useless is out now and available to order from Black Ocean.

Works Cited

Many thanks to Dr Michael Mayo and his Capital reading group.

di Prima, Diane, 1998. Memoirs of a Beatnik (London: Penguin).

Joyce, James, 1986. Ulysses, ed. by Hans Walter Gabler (London: Vintage).

Marx, Karl, 1992. Capital: Volume 1., trans. by Ben Fowkes (London: Penguin).

Min Jeong, Kim, 2020. Beautiful and Useless, trans. by Soeun Seo and Jake Levine (Black Ocean).

Min Jeong, Kim, Soeun Seo, Jake Levine, and Park Joon, 2020. ‘I’ll Do What I Want: A Conversation with Kim Min Jeong.’ The Margins [online]. 21 October 2020. Available at: <https://aaww.org/ill-do-what-i-want-a-conversation-with-kim-min-jeong/>.

~

Text: Katherine Franco

Published: 13/4/21

Comments